Open-sourcing your developer tool does make it a little easier for you to gain market share and gain goodwill within the community, but it does bring with it the risk of copycats.

And, if you do decide to monetize your open source project down the line, you might run into a situation where a much larger competitor simply forks your repository and starts their own project, putting you at a disadvantage. Bryan Cantrill called it the “open-source software midlife crisis”. Monetization attempts via relicensing have historically not gone down well with the developer community either, as is evident with the reaction to MongoDB, Elastic and CockroachDB. Even if you do have a paid, hosted option separate to your free, open-source product, a subset of your audience will believe that you are making the open-source version worse intentionally.

Because, open-source projects tend to offer the code for free, people expect the support to be free as well. Maintainers might end up burning out while trying to deal with the flood of support requests without the necessary resources at hand, putting the project’s sustainability at serious danger.

So, you do need to monetize your product in some capacity if you’d like to continue serving the community. And as a bonus, you can also invest additional resources to keep improving your product, instead of relying on personal funds to keep going.

But, can you actually monetize open source software without alienating your audience or running the risk of IP theft?

Turns out you can. There’s 7 OSS business models you can keep in mind when trying to monetize your product.

Open Source Monetization Models

1. Open Core Model

Under the open-core model, you build and maintain two editions of your product: the core functionality as open-source (usually under an MIT or Apache-type license), and a source-available license with features designed for larger businesses. So, your customers can deploy the source-available edition on their own infrastructure, but they would need to pay you for those additional features. Adopt this model when you have a core product that solves a broad developer problem, enterprises need extra features like scale and compliance, and you’d like to preserve a contributor community while selling advanced capabilities to enterprises.

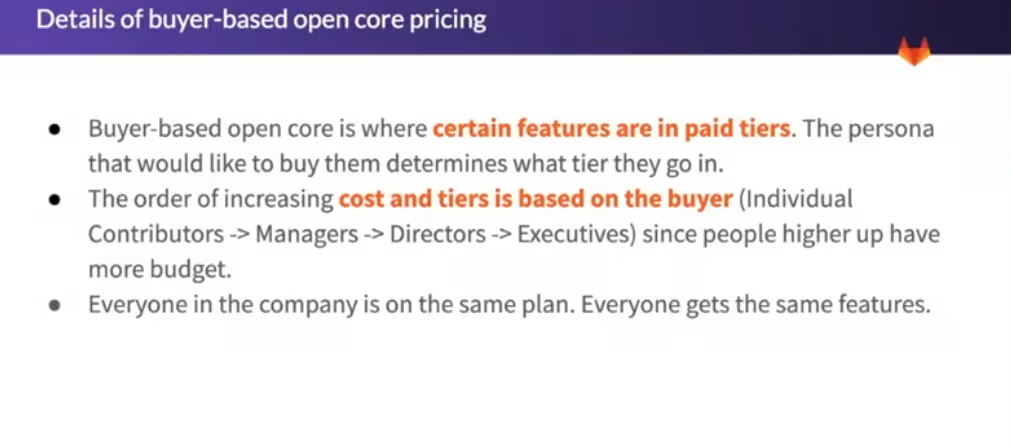

GitLab, for instance, opted for a buyer-based open-core monetization model, where they made the features proprietary based on which buyer they appealed to. So, if a buyer or the person that cares more about the feature is an individual contributor, you make them open-source. But, if the person is in management or is an executive, then you charge a good bit of money. This works pretty well because executives tend to be less price-sensitive with the budget authority to spend money on the proprietary features. For instance, according to their founder, a lot of their security features are proprietary because a CISF has the spending power to pay for it.

Pros

- Allows the company to continue benefiting from community contributions while providing a clear path to monetize enterprise customers.

- You don’t have to process data through third-parties, making it easier to gain adoption within enterprises that place a lot of value on data privacy.

- Is a good model to retain both contributor trust and adoption velocity.

Cons

- You have to build and maintain two distinct editions of your product, which means you’ll have to hire a larger, costlier engineering team, which means it might take you longer to get to revenue.

- Constant product management tension over what to gate. It also gets pretty difficult to keep the open-source and paid version separate without making users feel like the open-source version of the product is just a worse version of the paid version.

2. Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) Hosting

In this model, you sell a hosted version of your open-source developer tool. The revenue tends to come from either subscriptions (seat-based), usage-based tiers for compute or requests, or a hybrid model. It’s recommended to go ahead with this model when hosting provides a clear and immediate value, customers are more likely to offload ops to you, and you can automate and instrument billing, tenancy, and multi-tenant security.

Vercel is famous for using the SaaS hosting model to create a profitable business while keeping its core product (Next.js) completely free and fully open-source. The founder didn’t gate its capabilities or introduce usage restrictions allowing developers to use, self-host, or scale with it as they see fit. For companies that didn’t really have the inclination or resources to build and manage the infrastructure in-house, they could pay Vercel to host their Next.js app. Additionally, they used the revenue to fund further development of Next.js allowing them to keep growing without every forcing a sale.

Pros

- Scales revenue through recurring subscriptions.

- Easier to introduce usage-based pricing.

- Better control over product experience and upgrades.

Cons

- High operational cost and SRE burden.

- Need to solve data residency, trust, and compliance concerns to win enterprise deals.

- You’ll face stiff competition from hosting providers who simply host your free edition and charge their users for extra value-adds, cutting you out of the picture entirely.

3. Professional Services & Support

Open source software projects can also monetize by selling support contracts, consulting, managed services, or SLAs around their open-source tool. A common use case where this monetization model makes sense is when your tool is either mission-critical, complex, or requires expert configuration and maintenance and your customers tend to value expert operational help more than a hosted product. Common developer tools that use this model are messaging systems, databases, or clustered infra products.

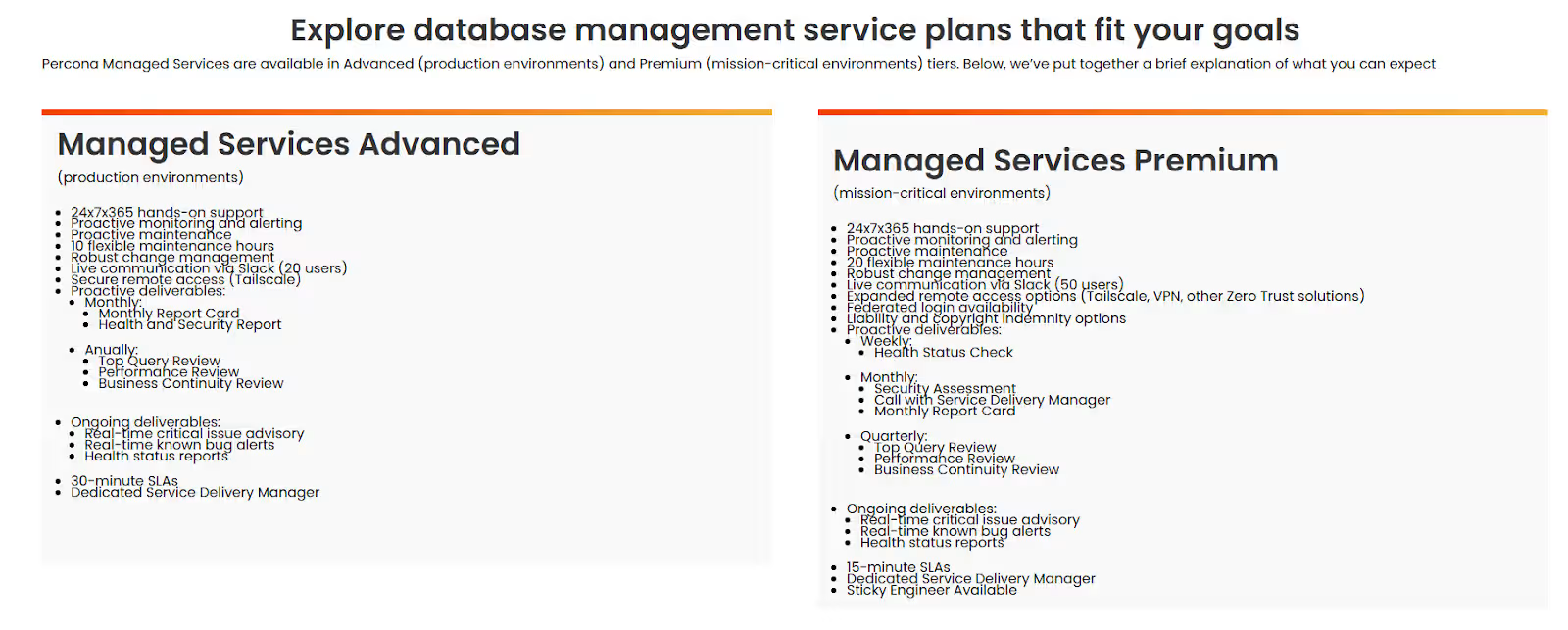

For instance, take Percona. They built a pure services and support business around open-source databases like MySQL, MongoDB, PostgreSQL, and Valkey/Redis. A couple of use cases where Percona’s managed services really shine are preparing databases for seasonal traffic spikes, emergency outage and critical issue resolution, future proofing your databases, ensuring uninterrupted performance, availability, and minimal disruption to production traffic while migrating to supported open-source databases.

Pros

- One of the fastest paths to revenue, provided your customers require immediate help with their setups.

- Low upfront product changes needed.

- Is a great model to strengthen customer relationships and retention.

Cons

- Revenue tends to be tied to labor, which could put hiring strain on your setup.

- You run the risk of losing focus on product development if you take on one too many customers tying up all of your time in providing support.

- Hard to scale profitably without productizing services.

4. Dual Licensing Strategy

Under this model, you offer the same code under two different licenses: a permissive or copyleft OSS license for the community and a commercial license for enterprises that want to avoid the OSS license restrictions or need commercial terms. BSL (Business-Source license) is a common open-source available license used by companies to protect cloud monetization. So, if you have intellectual property or network effects that some customers are willing to pay to license differently, or when your product is in direct competition with the big cloud providers, you can opt for this model. Unlike the open-core model where you have two codebases/feature-tiers and monetization comes from selling features, dual licensing’s monetization comes from selling rights and ships the same product under two different licenses.

A good example of a product that used this model is Confluent. It built its business around Apache Kafka licensed under the Apache 2.0 license, eventually using license and product segmentation to protect its cloud business and commercial products.

Pros

- Prevents bigger competitors from profiting off of your open source offering to create competing products.

- Direct commercial contract revenue from companies that need alternative licensing terms.

Cons

- Licensing tends to be a slippery slope. If you don’t explain the licensing changes and the reasons for it, you risk alienating the community. Source-available licenses are generally frowned upon by the community for products that claim to be open-source.

5. Premium Features & Add-ons

Also known as the freemium model, it allows you to offer a fully functional free core product and sell premium features or add-ons. This can be paid integrations, managed plugins, or in-product feature tiers. A common user journey under the freemium model tends to look like this:

Discovery → Onboard (free) → Power user (hits limits or needs team features) → Upgrade prompt → Paid onboarding → Expansion

When deciding the features you want to include as part of your commercial offering, you can focus on asking yourself the following questions:

- Does your product solve a core business problem or provide clear operational benefits?

- Is it hard to find reliable alternatives in your space? Is your offering hard to replicate? If so, that becomes your moat against larger competitors.

- Are there any at-scale capabilities required for organizations or teams that they can’t get from your open source offering?

Common features that open-source companies have generally included in a commercial offering are reliability, availability, security, better performance/faster throughput, more detailed dashboards/analytics, and multi-workspace collaboration. For add-ons, be on the lookout for recurring integrations requested by your customers that have tangible monetary value (either a direct or indirect impact to their bottom-line).

A good example of this tier would be Directus Cloud. Directus Cloud is licensed under the Business Source License (BSL) 1.1 with a permissive additional use grant. For most of its users and organizations with <$5M in annual revenue/funding, Directus is an open-source data platform that’s freely available and can be self-hosted. If, you plan on moving your project to the cloud, Directus Cloud provides a usage-based, self-serve offering that lets you create projects starting from $15/month. Additionally, you also get storage, auto-scaling, and a global CDN.

Pros

- Preserves community trust since the core product remains free and open.

- Monetizes extensions/integrations instead of forcing enterprise-only core features.

- Encourages ecosystem development by letting third-parties build add-ons as well.

- Pricing plans tend to be flexible because they are usage-based.

Cons

- Maintenance overhead to support add-ons.

- Conversion is reliant on finding strong value-market fit (valuable add-ons that users would be willing to pay for).

6. Community Sponsorship & Donations

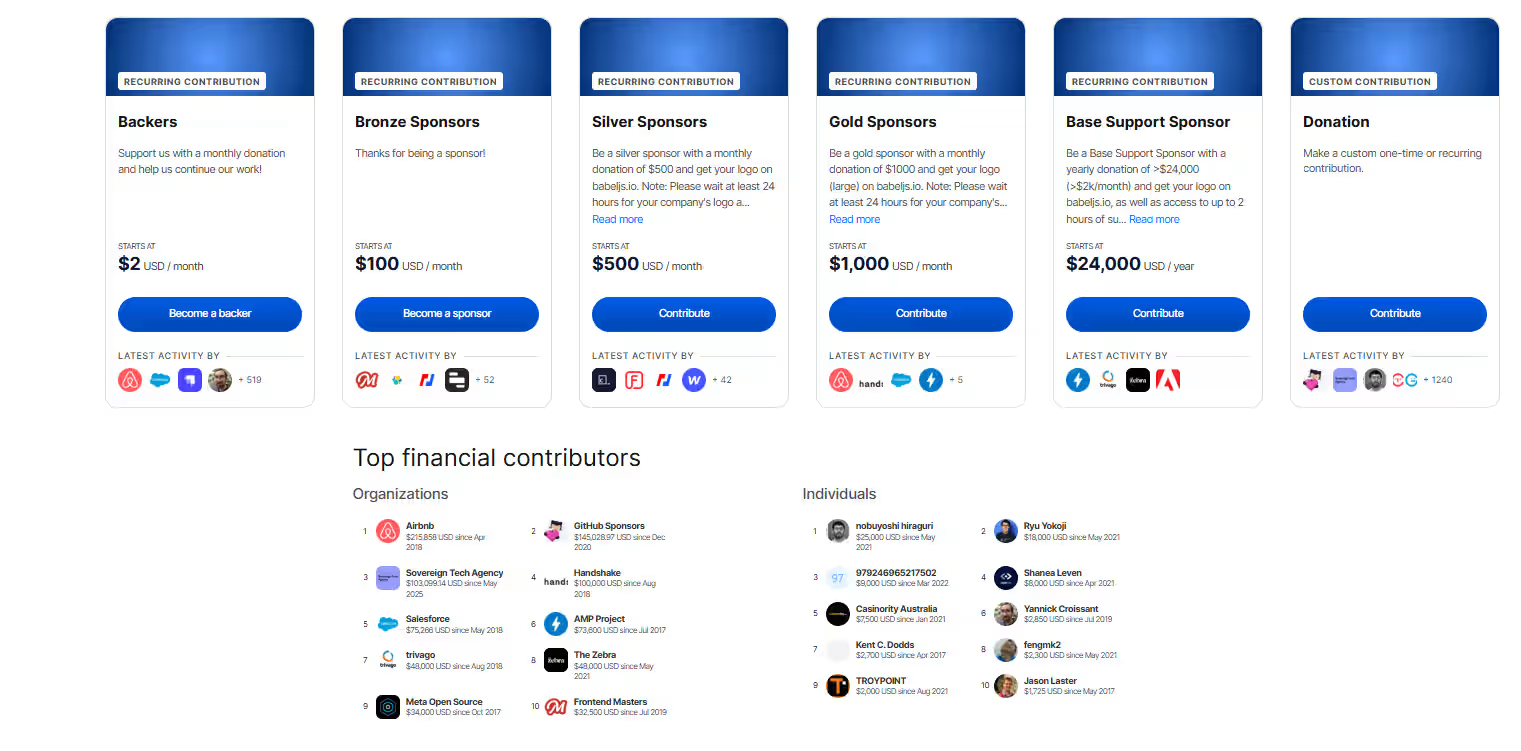

This happens to be the most common way to support OSS projects and their maintainers. For businesses, they might want to sponsor OSS projects to ensure they stay stable, up-to-date, and actively maintained. You can become a sponsored developer by joining GitHub Sponsors, which then allows you to accept donations through GitHub. OpenCollective is another great platform, used by Babel (community maintained compiler for Javascript) having raised over $1.4M till date.

Pros

- Lets you keep the project fully open, which means you’ll always have the support of your contributors.

- You don’t need a lot of operational overhead to get started. All you need to do is sign up to GitHub Sponsors or OpenCollective and start accepting donations.

Cons

- Usually, this model is not feasible if you plan on maintaining an entire engineering team on donations.

7. Marketplace & Ecosystem Revenue

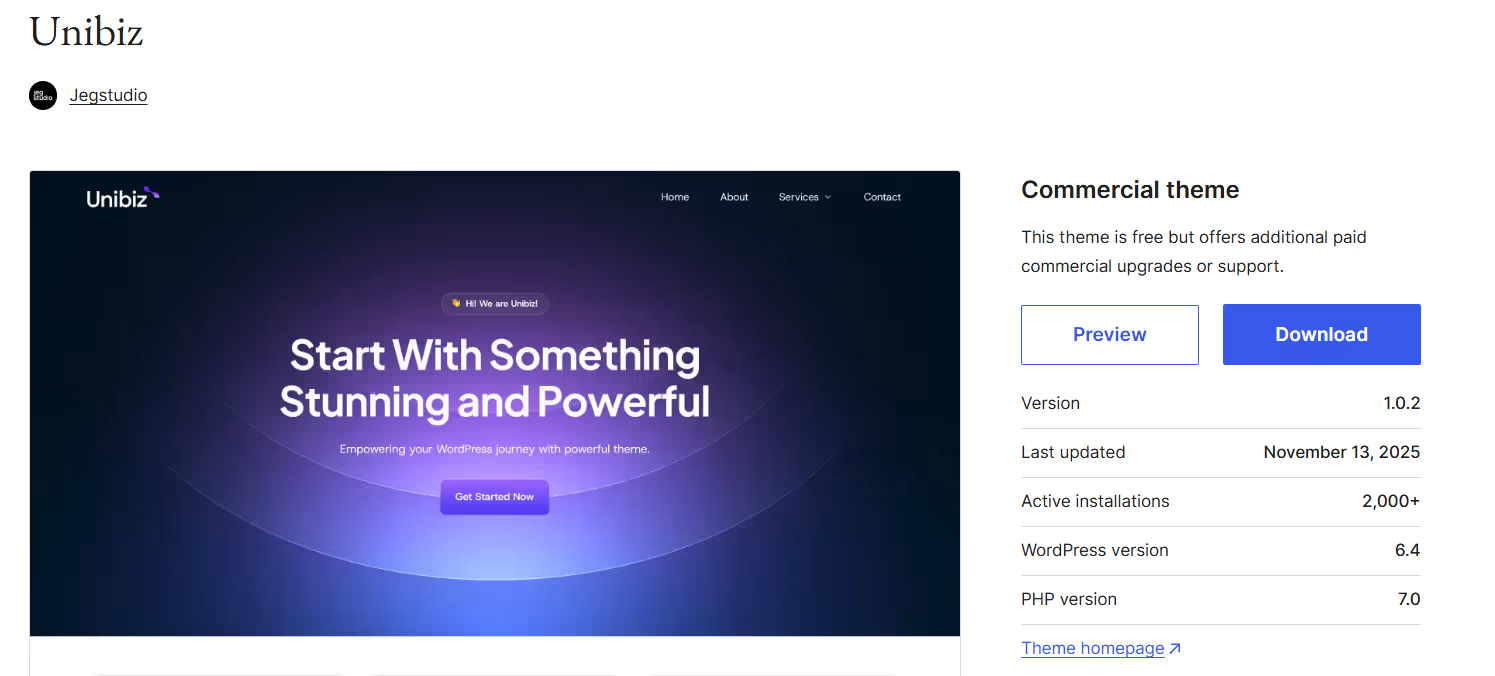

In this model, you monetize your product through a marketplace of plugins themes or integrations where third-party developers can sell extensions and you either take a cut of their earnings or charge platform or hosting fees. If your product is naturally extensible via plugins, themes, or modules and has a large install base and developer ecosystem.

A good example of a product that uses this model well is WordPress. Wordpress.org provides the core software for self-hosted websites, giving users complete control over their environment. While users can download and use the WordPress software for free, WooCommerce is one of the many profitable e-commerce plugins for self-hosted WordPress sites. While WooCommerce’s base plugin is free, it generates income through paid extensions and themes.

Pros

- Low internal developer cost since it relies on third-party innovation.

- Scales really well if the ecosystem takes off.

- Is a great way to create stickiness because plugins would create a migration cost for users.

Cons

- It requires investment in platform stability and discovery.

- Quality control and security overhead. If you’re strapped for resources, this might not be your best bet.

- Marketplaces tend to face the “cold-start” problem where you’d need two distinct set of users (buyers and sellers) for it to be valuable to either group. You might need to “recruit” one side of the market in order to get to “critical mass” of users.

To sum up the monetization models, here’s when you should use them:

- Open-core: Enterprise customers need add-on enterprise ops features and you want to maintain your open-source community too.

- SaaS Hosting: If hosting reduces friction/ops for users.

- Services/Support: If your product is a complex infrastructure tool and you want to get the ball rolling on revenue.

- Dual Licensing: If you need contractual commercial teams vs OSS license constraints.

- Premium Add ons: If you have a PLG product with natural team upgrades in place.

- Sponsorships/Donations: Useful as a supplement or if you prefer full governance.

- Marketplace: If the product is extensible and can host a theme/plugin economy.

Choosing the Right Monetization Strategy

There are no one-size-fits-all open source monetization model sadly. So, to understand which of the 7 strategies is the right fit for you, you need to keep the following factors in mind:

- Target customer segment: For developer tools, your user and buyer might not be the same person. Your monetization model needs to be picked by keeping your buyer in mind. So, if developers are your buyers, SaaS subscriptions are the way to go. If the buyer of your software are larger enterprises, it makes sense to go with enterprise contracts. If the enterprises also need hand-holding, you can layer on a support/services model.

- Product complexity and hosting requirements: Take a look at how your customers are using your product. Evaluate their compute needs, hosting and customer infrastructure access requirements, and operational burden for say clustering or observability. So, for instance, if your product is a modular, pluggable architecture, monetizing through marketplace add-ons would be ideal. Similarly, tools with deep kernel or infrastructure dependencies would require enterprise or service models to support them.

- Team size and technical resources: Your team size will actually determine if you can deliver on your promises. For an enterprise open-core monetization model, you would need a team of sales engineers, account executives, and customer success reps to close the deals. If you have a very small team with no SRE skills, SaaS might not be a great fit to begin with. You could try opting for donations/sponsorships instead, and as you expand, transition to a different model.

- Market competition and positioning: It is crucial to understand what you are going up against. This will give you a fair idea of what you need to do to position yourself in the market that differentiates you from the competition while providing the table stakes features. So, if your competitors are resorting to a SaaS model, a hosted, integrated cloud offering might be expected when you go looking for customers. If the category is pretty niche or emerging, using a services-led model to take your customers to their “aha” moment with your product could monetize your early adopters effectively.

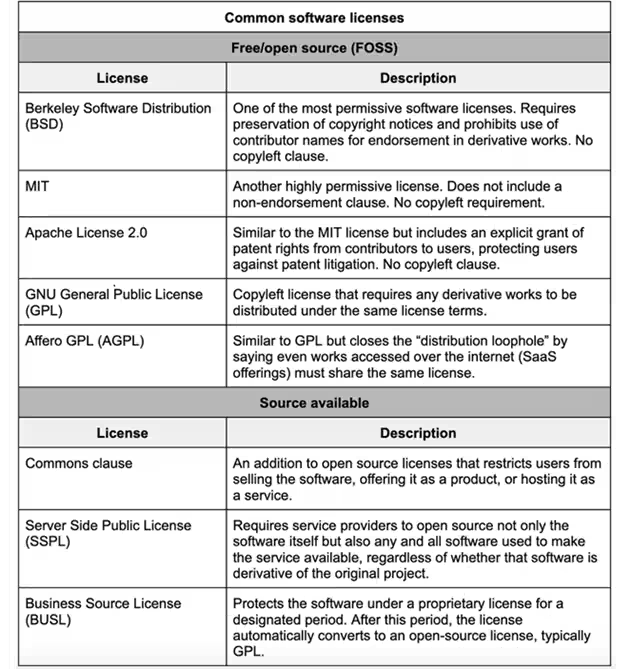

- Licensing philosophy and control: Developers care a lot about the openness of an open-source product/project, which means your licensing philosophy would limit the monetization models you can actually use. There’s 4 open source license types you need to be familiar with:

- Permissive: Allows users extensive freedom to use, change, and distribute the licensed software with minimal restrictions. Examples: MIT License, Apache License.

- Copyleft: Under the share-alike provision, any modifications or extensions need to be distributed under the same copyleft license terms. Example: GNU General Public License (GNU GPL)

- Weak copyleft: Facilitate compatibility with proprietary software, allowing linking or combining the code with proprietary software without requiring it to be released under the same license. Example: Mozilla Public License (MPL)

- Strong copyleft: Aims to prevent the creation of closed, proprietary derivates. Example: Affero General Public License (AGPL).

- Ecosystem surface area and extensibility: Some products have the capability to grow ecosystems, while others might be monolithic. So, if you have significant ecosystem traction, marketplace-based models are the way to go.

- Price sensitivity and value delivery speed: To understand your customer’s willingness to pay, you need to ask yourself a couple of questions:

- How quickly does the user see value? If the time-to-value is pretty small and the ROI seen by customers is pretty strong, a self-serve SaaS model is recommended.

- Is your product mission-critical or a nice-to-have? If it’s a mission-critical tool, you can go ahead with an enterprise friendly model or provide professional services to your customers.

- Are you replacing an expensive existing system?

- Does your tool require deep integration or would shallow adoption allow users to see value from it?

- Is your category extremely price sensitive? If so, you might have to rely on donations/sponsorships.

- Governance model: Your governance structure will restrict what monetization models are allowed and acceptable. So, let’s say your open-source software is governed by a foundation like CNCF or Apache. The monetization models most suited for you would be sponsorships, services, or through marketplaces cause foundation-governed OSS rarely support open-core or proprietary enterprise features. If the project is controlled by a single vendor, you have the flexibility to pick the model of your choice. On the other hand, if external contributors are major stakeholders in your software, you might have to rely on market-based ecosystems or donations.

The most common pattern for successful OSS companies is to combine an open-core model with hosting and services/marketplace as secondary and tertiary revenue streams. But, that doesn’t necessarily mean that your product should opt for the same structure. Pick one that fits your use case right now, and as you keep growing, see what other models you can stack on top of your initial model to continue growing. To get started, you can use the following table as a reference:

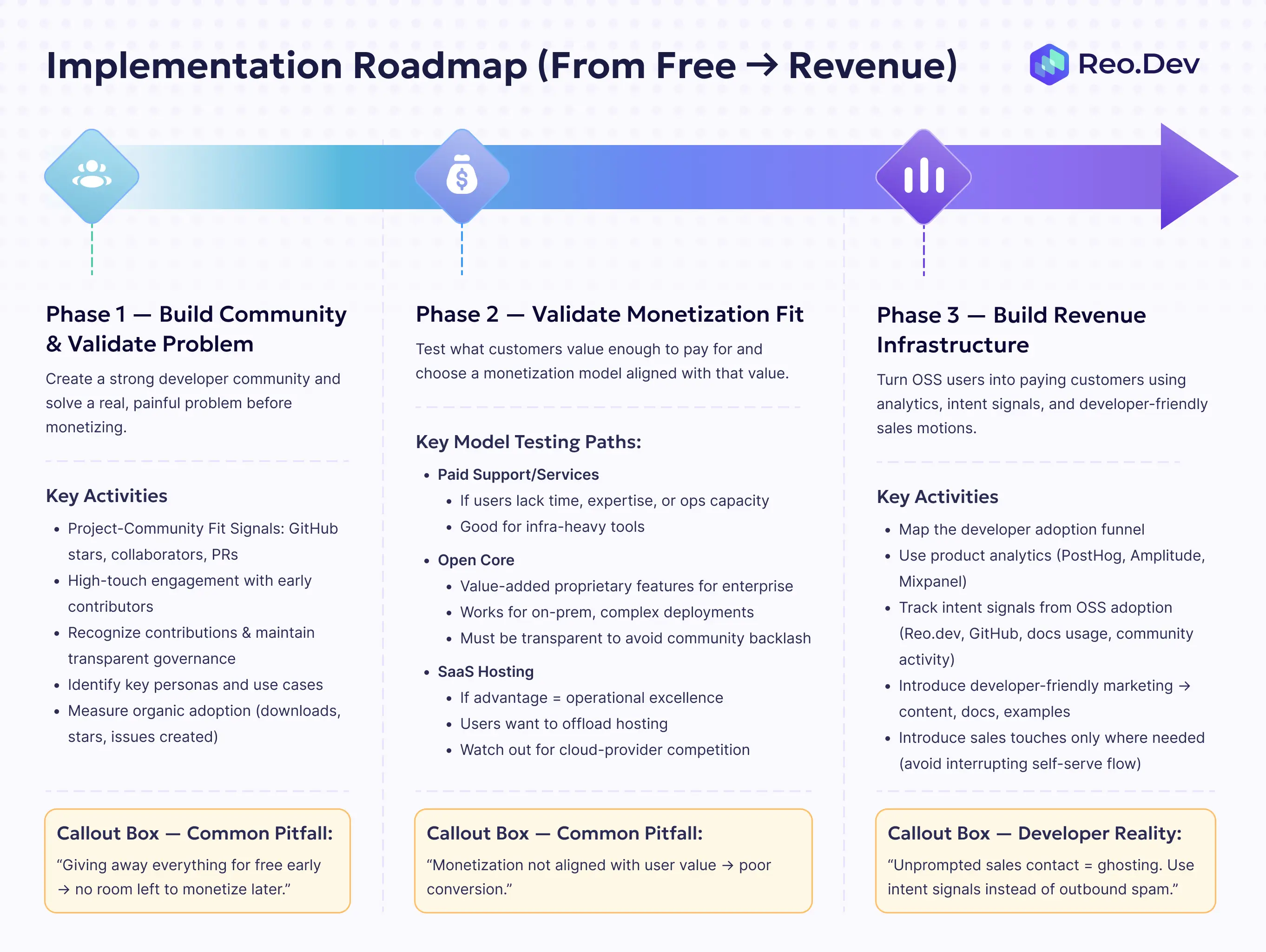

Implementation Roadmap: From Free to Revenue

Phase 1: Community building and product-market fit

Before you monetize your project, you need a community that cares about your product and a painful problem that your product solves.

Also called the project-community fit, key indicators that your OSS project is gaining strong interest among developers include GitHub stars, the number of collaborators, and the number of pull requests.

To achieve project-community fit, you need high touch engagement and continual recognition of the developer community, according to a16z. The best project leaders would focus on making clear decisions to provide project direction while making sure everyone’s voices are heard and their contributions are recognized. This balance ensures healthy growth of the project and attract more people to contribute to and distribute the project.

Once you have a project leader in charge of leading the OSS project and an active group of collaborators, you then need to understand product-market fit. By having a thorough understanding of the problems your OSS solves, your target audience, existing alternatives, you’ll start seeing organic adoption of your software within your community, which can be measured by the number of downloads.

A common pitfall that a lot of OSS products run into is not figuring out what they’d like to commercialize in the future. Without a concrete plan to deliver value that someone might be willing to pay for and giving it all away for free, there’s no room for a natural extension that can drive revenue. So, when you do try to monetize your product down the line, you’re gonna have to gate features that were previously free, which is bound to be met with pushback from the community.

Phase 2: Monetization strategy selection and testing

Value-market fit focuses on what customers care about and are willing to pay for. This would help you decide the monetization strategy you can pick:

- Paid support and services on top of free services and software. If you notice that your target audience consists of companies who lack the time, expertise, or inclination to deploy, use, maintain, or upgrade your software by themselves, you can provide them value by opting for this model. While popular in the open-source 1.0 era, this model has since dwindled over the years, primarily due to its lower margins.

- The open core model layers value-added proprietary code on top of your OSS, which can be a good model to choose for on-premise software. The biggest issues companies face when opting for this model is alienating the community by not being transparent with them, which is why it’s so crucial to think of a clear demarcation between what you plan on monetizing and what you would want to keep free when building up your community.

- You provide a complete hosted offering of your product in the SaaS model, which is a good pick if your value and competitive edge lies in the operational excellence of your software. Since SaaS tends to revolve around cloud hosting, opting for this model might put you in direct competition with the larger public clouds, which tends to get really murky.

Phase 3: Sales and marketing infrastructure

Your open source community would serve as the top-of-the-funnel leads for your value-added software products/services. After they’ve entered the funnel, your next goal tends to be maximizing developer and user love, value, and adoption, turning those free users into paid subscribers.

But, the usual marketing/sales strategies don’t usually work as well with developers, and any attempt to make unprompted contact with them in their self-serve journey might end up with them ghosting you. So, understanding the actual developer buyer/user funnel would be essential to understand the stages where marketing and sales can offer the most value and gently nudge them further in their journey.

Once you start incorporating sales and marketing activities to spread the word about your product and converting free users to paid subscribers, you should also incorporate product analytics to help you understand what percentage of OSS users will end up converting to buyers. It will also give you an idea whether your monetization model is actually working, or you need to pivot or layer on an additional model to get the desired results.

So, an ideal infrastructure to help you get the most out of your marketing, DevRel, and sales activities should include a developer intent signal tool that lets you track developer activity across key product pages, open source communities, and other relevant telemetry signals like Reo.dev and a product analytics tool like PostHog, Amplitude, or Mixpanel.

Maintaining Community Trust During Monetization

For an open-source software, community tends to be the most important lever of growth. One of the biggest risks that come with trying to monetize your software is alienating your developer community, who tend to be extremely wary of ‘bait and switch’ tactics, where a relicensing takes place to maximize monetization. While a lot of companies claim the relicensing move was required for company survival, the developer community still tends to feel a sense of betrayal, with the fear of impending vendor lock-in.

Here’s a list of common licenses adopted by developer tools today:

Most often, relicensing involves moving away from permissive free and open source licenses to more restrictive “source available” licenses, that allow access to the source code but impose restrictions on commercial use.

MongoDB, initially released under the AGPL license, started being used and offered as a service by a large number of cloud providers. MongoDB’s CTO and co-founder Elliot Horowitz felt that once open-source projects gained traction, it became way too easy for cloud vendors who hadn’t developed the software to capture all of the value while contributing little back to the community. As a response, MongoDB created the SSPL license and submitted it to the Open Source Initiative for approval, stating that the SSPL license builds on the spirit of the AGPL license, but under the SSPL any organization attempting to exploit MongoDB as a service needs to open source the software used to offer such a service.

The Open Source Initiative clarified that SSPL is not an open source license, stating quite clearly that software claiming that the software has all the benefits and promises of open source under such a license is “deception, plain and simple”. The community didn’t take MongoDB’s move too kindly either.

Redis also went through something similar, trying to prevent larger cloud providers from profiting off of its product, and relicensing from the more permissive BSD license to the Commons Clause for a portion of their product. A strong negative reaction from the audience caused them to retire the Commons Clause in favor of a new RSAL (Redis Source Available License) in 2019.

The story seems to run along similar lines for Elasticsearch and CockroachDB as well.

Where did they go wrong?

Trying to prevent larger players from profiting off of their IP without paying a dime was something everyone understood, but where the community seems to have drawn the line was the companies trying to pass of these new “source-available” licenses as open-source/free software.

They demand transparency. If you want to prevent others from exploiting your hard work, then feel free to go with a proprietary license, but pretending that a proprietary license is open-source brings certain expectations with it (including being okay with people using it as they see fit, as defined under the guidelines for free and open-source software licenses).

Here’s how GitLab managed to maintain community trust while relicensing their software:

- Transparent communication: They addressed the community’s open-core fears upfront. They licensed the GitLab Community edition under the MIT License, an official OSI-approved open source license as opposed to the source-available license route taken by its contemporaries. To further reinforce their commitment to open-source, GitLab also made the public promise that no open-source features would ever be moved to paid tiers. They also allowed contributions for existing paid features, and based on their publicly available evaluation criteria, they would evaluate to see if the feature would be better off as an open-source feature instead. This way they ensured the wider community felt they had ownership over the product.

- No vendor lock-in: A major concern with open core tends to be its premium features. Users believe it might make it hard for them to switch or integrate with other tools. GitLab tackled this by providing open integrations and extensibility along with APIs for almost every feature, compatibility with external DevOps tools and flexible deployment options.

Conclusion

We discussed the most common open source monetization models, but there’s no perfect strategy out there. It always boils down to a process of trial and error. Use the factors we listed in this article to understand what’s the best model for your product right now. You need to understand that this is still just a starting point. As your product and company evolves, so will the monetization model. For most of the products discussed in this article, they have a hybrid model that relies on a combination of the models we’ve discussed (open-core + SaaS hosting, freemium +community sponsorships/donations, to name a few).

But as long as you are transparent with your community and continue building your product while keeping them at the center of it, your community should be fine with you monetizing the product, which is crucial if you want to keep the OSS project going.

How Reo.Dev Can Help You Track OSS User Adoption

We are helping 100+ companies track OSS user adoption similar to GitLab and Vercel.

We help developer tool companies capture all the ways devs interact with your open-source codebase, allowing you to separate the enthusiasts from the enterprise evaluators and optimize your GTM strategies accordingly.

Want to see which dev teams are actually interacting with your OSS projects? Get a live walkthrough of Reo.dev for your DevRel team and start tracking OSS user adoption today.

{{product-blog-banner}}

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Open Source Monetization Matters for DevTools?

Monetization matters because it lets DevTool creators to:

- Invest in long-term reliability (bug fixes, patches, version upgrades).

- Build enterprise-grade features that individual contributors don’t need but companies will pay for.

- Support critical workflows like scale, performance, compliance, and integrations.

- Fund DevRel, docs, and community programs that accelerate adoption.

- Compete against cloud vendors who can otherwise host your free version and capture the value.

How can you monetize open source software?

There’s 7 OSS business models you can use to monetize your product:

- Open-core

- SaaS Hosting

- Professional Services & Support

- Dual Licensing Strategy

- Premium Features & Add-ons

- Community Sponsorship and Donations

- Marketplace and Ecosystem Revenue

What are some leading indicators which tells me I’m ready to monetize my open source software?

Be on the lookout for these things:

- Consistent GitHub stars growth

- Frequent PRs from external contributors

- Increasing downloads or monthly active deployments

- Companies asking for support or SLAs

- Users requesting at-scale or team features

What tools should I use to understand when users are ready to pay for my open source?

To understand if developer adoption could translate into actual revenue, developer companies typically use a combination of product analytics tools(PostHog, Mixpanel, Amplitude) and developer intent signals (Reo.dev).

How do I decide what should be free vs. what should be paid for my open source software?

As a rule of thumb, if your software’s features are being used by individual developers, contributors, and hobbyists, keep them free. Monetize the features that are needed for scale, compliance, security, governance, multi-team workflows, reliability, performance, or enterprise operations. An easier way to look at it: If an executive cares about it, it usually belongs in the paid tier.

When should I not monetize my open source software?

Don’t rush to monetize your open source software if:

- Project-community fit is not established

- You don’t know your target buyer or your user ≠ buyer

- You’re struggling with governance disputes

- You haven’t identified what unique value you can actually charge for

- Trying too early may stall adoption and hurt contributor trust.

References: https://a16z.com/open-source-from-community-to-commercialization/

How do open source projects make money?

Open source projects can generate revenue by layering commercial value on top of their free community edition. The most common methods include offering enterprise-only features, hosted SaaS versions that reduce operational burden for users, paid support or consulting, commercial licensing for companies that want different legal rights, selling premium add-ons or integrations, and even building a marketplace for third-party extensions. The key is keeping the OSS core valuable and free while monetizing capabilities that solve real business problems at scale.

What are the best business models for monetizing open source?

Developer tools typically succeed with seven monetization models: open-core licensing where enterprise-grade features are paid, SaaS hosting where users pay for convenience and uptime, professional services and support for mission-critical setups, dual licensing when enterprises need proprietary terms, premium features and integrations for power users, community sponsorships for solo-maintained projects, and marketplace revenue when a large ecosystem forms. Successful companies often combine two or more of these models as they grow.

How do I choose the right monetization model for my OSS product?

The right strategy depends on who your buyer is, how complex your product is to run, and what users value most at scale. If enterprises need compliance, governance, or security features, open-core or dual licensing works well. If users want to avoid running infrastructure themselves, a hosted SaaS version creates a strong value exchange. If expert assistance is the biggest need, support and consulting can be the fastest way to revenue. Start with the lowest-friction model that aligns with how users already adopt your product, then layer others later.

Can you monetize open source without upsetting the community?

Yes, as long as you are transparent about what remains free vs. what becomes paid, and avoid taking previously free features away. Developer communities support monetization when they believe it improves the project’s long-term sustainability, maintains openness of the core, and avoids vendor lock-in. Clear communication about licensing philosophy, contribution rules, and the project’s commercial roadmap helps preserve trust even as the business grows.

What is the easiest way to start making money from a new open source tool?

The fastest path to revenue usually comes from paid support or setup services because companies are often willing to pay for faster onboarding even if the product is free. As adoption grows, you can introduce hosted SaaS options, feature tiers, or premium services based on what users show willingness to pay for. Starting with services allows you to validate commercial demand before building complex infrastructure.

How do I protect my open source business from cloud providers copying my product?

Dual licensing or source-available licenses can prevent cloud vendors from reselling your work without contributing back. For example, BSL and SSPL variants offer more commercial protection while still allowing access to code. Clear governance decisions early on help you avoid painful relicensing later and preserve trust with your community while protecting your long-term business advantages.

Can I monetize my open source project if my users prefer to self-host?

Yes. Many enterprise buyers want to keep their environments private but still need advanced capabilities like security, reporting, or scale. An open-core model lets self-hosted users run the open version for free while paying for proprietary enterprise plugins or operational features. Commercial licensing and long-term support contracts also create revenue while respecting their hosting requirements.

Is professional support a viable monetization path for open source?

Paid support and managed services can generate revenue quickly, especially if your tool is complex or mission-critical. Organizations may value expert help with deployments, performance tuning, migrations, and SLAs, which turns your knowledge into a revenue stream. However, scaling this model requires headcount and can divert attention away from core product development unless services are eventually productized.

What features should I monetize in an open source developer tool?

Anything tied to enterprise value—rather than hobbyist use is generally fair to charge for. These include advanced security and compliance controls, performance scaling, governance features, team collaboration, analytics, managed infrastructure, and integrations with other business systems. A useful heuristic is: if an executive or procurement buyer cares about a feature, it belongs in the paid tier. Keep the core workflow open so developers can continue to adopt and champion the product without friction.